Is this the worst etiquette mistake you can make on the golf course?

Horace Hutchinson was one of Britain’s most decorated amateur golfers and a famous Victorian writer. But he was faced with an issue we still debate to this day. Steve Carroll explains

If you’ve never heard of Horace Hutchinson allow me to illuminate you. His name is about to leap off this page.

He was an absolute titan of Victorian golf. Heard of the Amateur Championship? Hutchinson played in the first three finals, winning it twice and famously beating John Ball on his home track of Hoylake to defend his title in 1887.

He was also a voracious writer and the author of two of the bibles of that era: British Golf Links and the Badminton Library on Golf.

It’s the latter we’re going to flick through because this incredibly detailed tome, which includes essays on clubs, balls, instruction, and the history of the game, also included a quite brilliant chapter on etiquette and behaviour.

Turns out old Horace had quite a lot to say about what was acceptable during a round and it’s a fascinating insight into the culture of a bygone age. He was even more strident on what wasn’t.

The things that get us really riled up today – pitch marks on greens and raking bunkers – didn’t register at all in his era.

There is a brilliant passage on gimmes – “Perhaps one of the most offensive of all breaches of etiquette is committed by him who, after missing one of these little putts, says to his opponent, airily, ‘Oh, I thought you had given me that!’” – and rather too much time spent on people who poke their clubs into sand in the bunker.

What really got Hutchinson’s goat was people who stood over him “with triumph spiced with derision” and counted out his score as he hacked away in a bunker.

But this was all rather small beer. There was one other faux pas that sent him into spasms and it’s described with such beautiful eloquence that it might go down as the worst etiquette mistake you could make on a golf course.

Ready? For this titan of a nobler age, this was the ultimate sin: “No golfer is worthy of the name who does not put back his divot.”

“After all, what is courtesy but unselfishness and consideration of others,” Hutchinson opined. “How grossly then does not he offend against every dictate of courtesy who scalps up the turf with his heavy iron, and leaves the ‘divot’ lying, an unsightly clod of earth, upon the sward!

“What shall we do to such as he, as, playing after him, our ball finds its way into the poor dumb mouth of a wound which he has thus left gaping, to call down upon him the vengeance of gods and men?”

It’s hard to say whether Hutchinson would join the modern clamour for free relief from such a fate. He notes with some exasperation that our rules say it is a player’s first duty to replace a divot, but that in spite of all those efforts “the scalps and divots still lie unsightly on the links… though we curse with bell and book and niblick the sacrilegious villain who left the raw, gaping wound on the sacred soil”.

Utterly confusing for Hutchinson, just as it is today, was how easy it was to remedy the problem. Simply put it back. Although he, of course, expresses it in much grander and loquacious terms.

“A divot well replaced is, in most conditions of the ground, as a divot that has never been cut.”

Wise words now, as they were 132 years ago when they were first published. Maybe one day, enough of us will take heed of them.

What do you think about the replacing divots debate? Are Horace Hutchinson’s complaints as valid today as they were more than a century ago? Let me know your thoughts with a tweet.

More on golf’s replacing divot debate

- NOW READ: You’ll never guess which rule this legend wants to change!

- NOW READ: Ball in a divot? Here’s the world’s smallest violin playing just for you

- NOW READ: Golf’s great divot debate – should you get free relief?

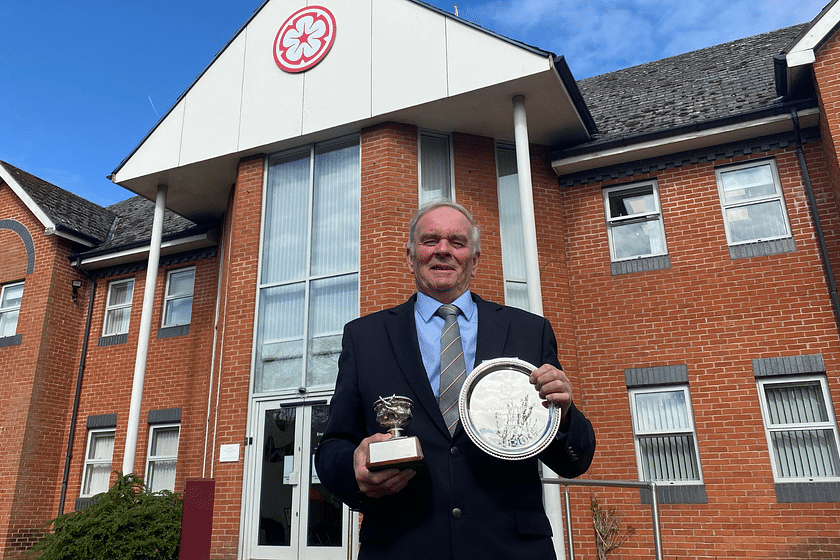

Steve Carroll

A journalist for 25 years, Steve has been immersed in club golf for almost as long. A former club captain, he has passed the Level 3 Rules of Golf exam with distinction having attended the R&A's prestigious Tournament Administrators and Referees Seminar.

Steve has officiated at a host of high-profile tournaments, including Open Regional Qualifying, PGA Fourball Championship, English Men's Senior Amateur, and the North of England Amateur Championship. In 2023, he made his international debut as part of the team that refereed England vs Switzerland U16 girls.

A part of NCG's Top 100s panel, Steve has a particular love of links golf and is frantically trying to restore his single-figure handicap. He currently floats at around 11.

Steve plays at Close House, in Newcastle, and York GC, where he is a member of the club's matches and competitions committee and referees the annual 36-hole scratch York Rose Bowl.

Having studied history at Newcastle University, he became a journalist having passed his NTCJ exams at Darlington College of Technology.

What's in Steve's bag: TaylorMade Stealth 2 driver, 3-wood, and hybrids; TaylorMade Stealth 2 irons; TaylorMade Hi-Toe, Ping ChipR, Sik Putter.